By Paolo Velilla

The past few months have been one of utter chaos in the United Kingdom. Alongside the skyrocketing gas and energy prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was political turmoil in the House of Commons. The British government has essentially hit the panic button, having had three prime ministers (PMs) in the span of only 52 days.

On September 6, then PM Boris Johnson was forced to resign by his party, the conservative Tories. This resignation was caused by several scandals and allegations against Johnson and members of his government, such as hosting social gatherings harshest days of COVID-19 lockdown—known as the “Partygate”,—and later the allegations of sexual misconduct made against Chris Pincher, a man whom he appointed to serve as Deputy Chief Whip.

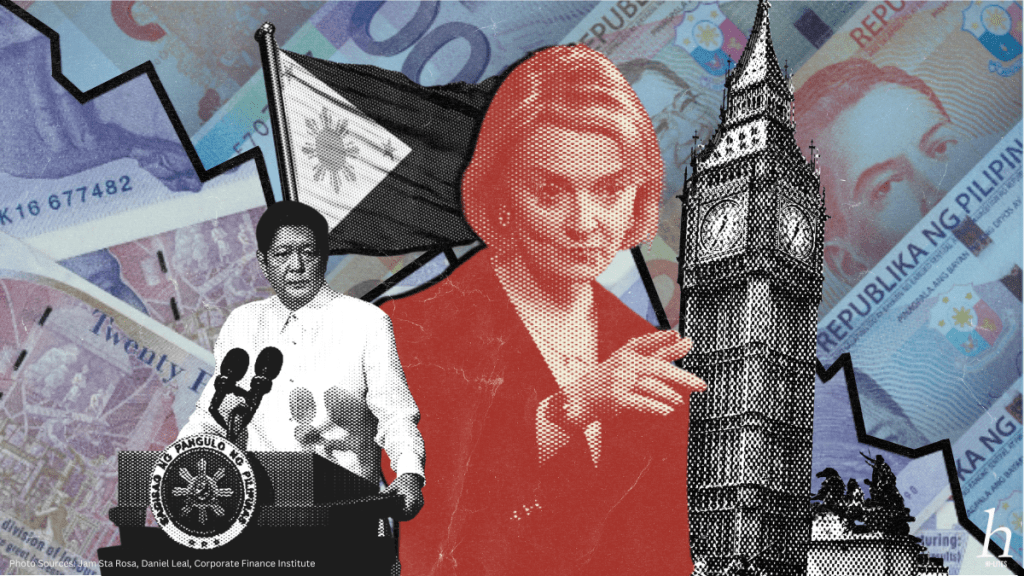

In replacement of Boris Johnson was Liz Truss. Once work resumed after the mourning period for Queen Elizabeth II, it was clear that her policies exacerbated problems. The government had to resort to borrowing money to make up for her promised tax cuts, which resulted in skyrocketing inflation; hence, higher interest rates, and a weakened pound that reached lows of $1.0899. She would later revert these changes, but the consequences of her actions made her unpopular with both the public and her own party. Then, on October 20, she too announced her resignation after 45 days, making her the shortest-serving PM in British history.

The following week, Rishi Sunak, who placed second to Truss in the leadership election to replace Johnson, stepped into Downing Street as the next PM, and still holds the position to this day. In a debate against Truss during the said election, he stated that, “if we just put fuel on the fire of this inflation spiral, [we’ll all end up] with higher mortgage rates, savings and pensions that are eaten away, and misery for millions,” foreseeing the consequences of Truss’s plans.

On the other side of the world, the Philippines is encountering similar problems. Skyrocketing inflation rates, a plummeting currency, and record-high gas prices are familiar words to the eyes and ears of the Philippine public. It is easy to see Britain’s ability to oust incompetent leadership, and potentially envision a version of the Philippines under a parliamentary system, but of course, it is not as easy as it sounds.

In a parliamentary version of the Philippine government, national positions have to be determined either by senate or congressional results. Based on the associated parties and senatorial slate of the UniTeam Alliance, it is clear that President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has the political majority to remain in power. The Lakas-Christian Muslim Democrats party led by Vice President Sara Duterte currently holds more seats in the house of representatives than any other party, at 66. Meanwhile, half of the 2022 election’s elected senators were a part of the UniTeam senatorial slate, such as Robin Padilla, Loren Legarda, and Win Gatchalian. In fact, only one person in the senate is in clear opposition to the administration, Senator Risa Hontiveros, essentially making her the leader of the opposition in this current government.

Based on the current structure of the UK government, alongside a hypothetical PM Marcos would be a Deputy Prime Minister Duterte, who will likely retain her status as secretary of education, with a cabinet not too dissimilar to what is currently present.

One of the features of the British Parliament that would raise a lot of questions is how a person such as Marcos Jr. would perform in Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs), a weekly broadcasted event where any member of parliament, including the opposition, can directly ask the Prime Minister, all of which must be responded to or answered by the PM. It is the test of a leader’s rhetoric, to show how exactly they would respond when confronted with a wide range of issues. When a scandal or controversy breaks out about the PM, the leader of the opposition is usually quick to remind the public about it. Liz Truss was lambasted by opposition leader, Keir Starmer during her final PMQs as prime minister, which led to the now infamous “I’m a fighter, not a quitter” response from Truss, a day before she announced her resignation.

Marcos Jr. was notorious for openly refusing to attend debates during the campaign season, and even in office, he is no stranger to offering indifferent and even confusing remarks to the public. How would a leader who “disagreed” with the county’s 6.1% inflation rate perform when tasked with answering questions regarding various national issues, in front of the entire Philippine public? It is not difficult to imagine the head of state giving the same questionable, shallow remarks when presented with real issues, but now on a mandatory weekly basis.

So, would a Marcos resignation be inevitable under a parliament? Well, not exactly, as there are factors specific to the Philippines that must be considered when discussing this issue.

One of the large factors that contribute to a PM’s resignation is public opinion, as a party would be likely to oust someone who is unpopular with the public. Polling results from Politico show that Truss had a record-low approval rating of -68% prior to her resignation. BBM, on the other hand, has had more favorable numbers, with his administration receiving “majority approval ratings” on 11 out of 13 issues during his first 100 days in office, according to a Pulse Asia survey.

One may ask: why is there such a discrepancy in results? The difference between countries lies in the freedom the government allows them to have. Britain is currently ranked 24th in the World Press Freedom Index, while the Philippines is all the way down in 147th place. While the largest news outlet in Britain is the long-standing and publicly owned BBC, the largest media company in the Philippines, ABS-CBN was forced by the government to shut down its broadcasting operations during the thick of the global pandemic. The government seemingly has a tight grip on what the press can and cannot say, which profoundly influences how the public perceives said government. Having a noose hanging above the heads of journalists and news outlets influences the information they want to spread. Writers and broadcasters are scared of meeting the same fate as ABS-CBN, and are thus unable to speak up when it is supposed to be their job to tell the things that the government won’t say.

Thus, if public opinion won’t be a cause for Marcos Jr.’s resignation under a parliament, then it has to be through the party itself choosing to oust him. The problem with this, however, is that the amount of nepotism and cronyism has tossed away any form of checks and balances in this government. To give examples, his sister, Imee Marcos, is currently seated in the senate, and the current speaker of the house, Martin Romualdez is his cousin. Anton Lagdameo, who was his campaign’s largest donor, is now currently serving as the Special Assistant to the President. The list of known members of government that will actively continue to support the Marcoses is never ending, which would make the possibility of more than half of his party siding against him, unfortunately, near-impossible.

But even in the event that he does resign, then who will be next? The next person in line would have to be his running mate, Sara Duterte, especially since rumors about her running for president swirled before even deciding to run as VP. She has the popularity within the party to take over in the event of Marcos’s resignation, because—keep in mind—it is the party that decides the next leader in parliament, not the people. So, the son of the most controversial president in Philippine history would end up being replaced by the daughter of yet another contentious former chief executive in this nation’s history.

In the end, the Philippines under a parliamentary system would not look too dissimilar to what the country has now. It does not matter what system the country employs if the country’s very foundation remains broken. The issue is not the system in particular, but the people running it. A lack of press freedom, a system infected with cronies, and a government run by people who care only about themselves, are issues that persist in the Philippines regardless of its system.