By Scott

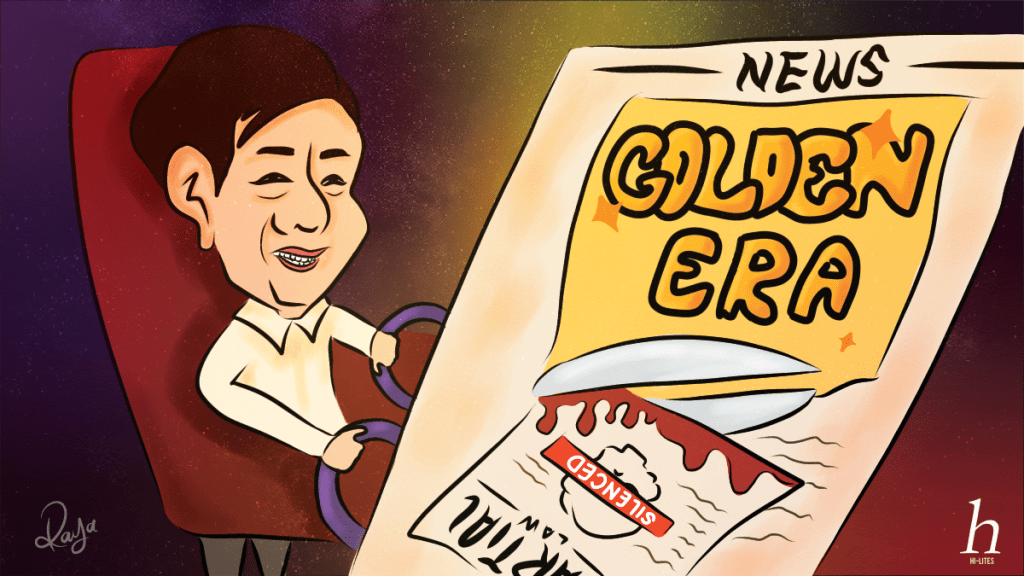

More than half a century has elapsed since the ominous era of Martial Law left its indelible mark on the Philippines. As we engage in introspection regarding our country’s trajectory, a disheartening reality becomes evident: while the Marcos family seems to be making large strides in the present, those who bore the brunt of this turbulent chapter in our history appear to have been left in the shadows.

The despair intensifies with the recent memorandum from the Department of Education’s (DepEd) Bureau of Curriculum Development (BCD), which mandates changes in the Grade 6 Araling Panlipunan curriculum, specifically altering the nomenclature related to the Martial Law years. In this memorandum, the BCD specifically ordered a change in terminology, shifting from “Diktadurang Marcos” to simply “Diktadura,” in an effort alleged by critics to disassociate the late President Ferdinand Marcos from the authoritarian rule that defined his time in government.

Each passing year echoes with the resounding cry of “Never forget, never again.” However, it is disheartening to witness that those responsible for these events continue to evade accountability. This leaves us pondering how we might be inadvertently engaging in hypocrisy, as both the citizens and the institutions of the Philippines continue to reflect the very patterns that defined Martial Law—a phenomenon that often eludes our awareness.

Through Different Lenses

One noticeable aspect of this year’s commemoration is how the accounts of victims are seemingly morphing into mere statistics and myths, gradually exposing how some individuals are erasing the memory of the tumultuous era that was Martial Law. Paradoxically, it is ironic how the consequences of Martial Law persistently infiltrate diverse systems, rendering this commemoration rife with empty gestures.

One glaring facet of this lies in our education system, which came to light in October 2022. This controversy stemmed from the publication of a Senior High School Module titled, “21st Century Literature from the Philippines and the World Quarter 1 – Module 1: Geographic, Linguistic, and Ethnic Dimensions of Philippine Literary History from Pre-colonial to the Contemporary.” The module attempted to redefine the years under Martial Law as the ‘period of the new society,’ revealing a concerning lack of foresight on the part of the education authority in ensuring a factual historical account of the Marcos dictatorship, while potentially enabling its propaganda.

In the business sector, there is also the presence of crony capitalism, where businesses and entrepreneurs cultivate close—and often corrupt—relationships with government officials or politicians to secure preferential treatment, akin to certain characteristics of a dictatorship. In The Economist’s most recent index, the Philippines was ranked fourth in the world for crony capitalism in 2021. This reflects the imbalance in the country’s economic landscape, where equitable opportunities are not extended to both small-scale entrepreneurs and large conglomerates. Instead, a select group of influential businessmen reap the benefits of a rent-seeking system, while smaller enterprises continue to grapple with significant challenges independently, echoing the pattern of wealth disparity seen during Martial Law when the rich became richer and the poor became poorer.

Timely enough, just one day after the observance of the 30th World Press Freedom Day in 2023, the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) released a report regarding the 75 cases of violations against media workers since President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. took office. These incidents occurred between June 30, 2022, and April 30, 2023, and encompass a range of offenses, including 40 cases of intimidation, 10 instances of libel and cyberlibel, 7 reported cases of harassment, 6 incidents involving journalists being barred from coverage or facing censorship, 5 instances of threats through messages and online, 4 reported cyberattacks, and 1 case of physical assault. This report underscores a remarkable parallel between the actions of the son and those of his father during Martial Law. Much like his child, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. utilized strategies including media shutdowns, the seizure of private media organizations, arrests of journalists and media proprietors, expulsion of and visa denials for international reporters, and the elevation of media outlets under the Marcos administration’s sway to shape public narratives.

These are just a few examples that emphasize that Martial Law is far from forgotten, regrettably not in the way that inspires us to build a nation committed to avoiding a repetition of history, but as a reminder that the values cultivated during that era continue to permeate our contemporary systems. Consequently, this underscores the importance of not only advocating for social justice, particularly when commemorating Martial Law, but also of ceasing to ignore the very systems and practices that bear resemblance to that dark period and that continue to persist within our society.