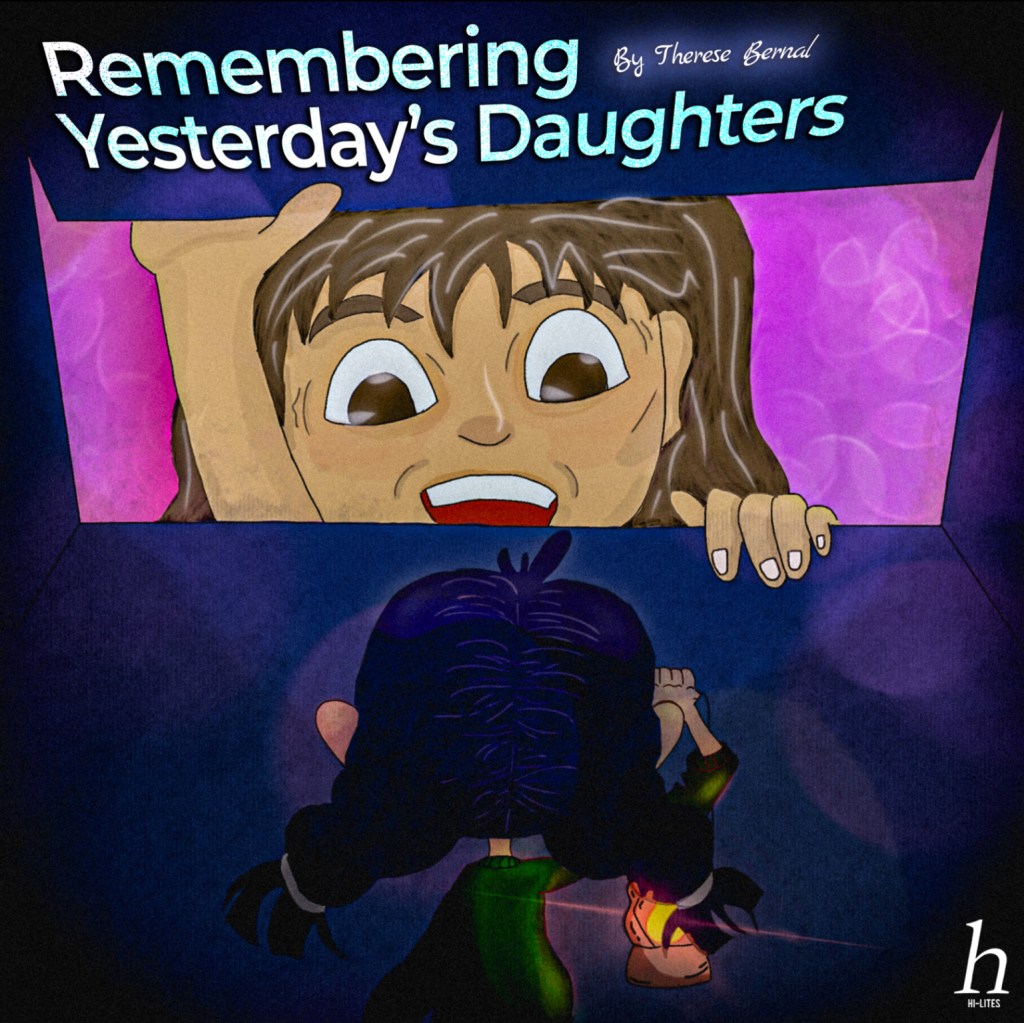

By Therese Bernal

Growing up, I find my mother’s criticisms to be the most scathing. She will watch me with eyes that have witnessed a similar scene firsthand, and I will shrink in awkwardness and embarrassment. When she begins to lecture me, her wisdom will come off as arrogance, and my shame will grow into anger. The same story will go with my grandmother, my aunt, my teachers, and the unending list of women who have become, in my eyes, held in such high regard—it becomes hard to imagine them as anything else than perfect.

However, as the years pass, time will reveal cracks in what was once an impenetrable image of impeccability and grace. Although just as forward and domineering, my mother will mellow down little by little, drop hints of her old memories and missed ambitions, and allow me to catch slight glimpses into her vulnerabilities. Meanwhile, I will slowly come to realize that maybe we aren’t so different—that perhaps, beyond those years, was the same little girl who needed to brave a world inherently engineered against her favor.

To Yesterday’s Daughters:

What does it mean to be a girl? As a toddler, slurring giggles and feebly crawling on awkward feet, there wasn’t really much to the world outside of the simplest, barest of things. Soon, however, the moment your hair was long enough to tie into pigtails, your limbs became a little stronger, and your speech became a little more sound—things would begin to change.

- I’m sorry that you had to choose.

“Bakit ‘yan nilalaro mo? Panlalaki ‘yan.” Comes a frequent remark, toeing the line between jest and judgment. You might feel a tinge of embarrassment, but it is relatively harmless. However, the adults will begin to spew out the similar rhetoric every now and again, often enough that your cousins and playmates will begin to follow—and the first cracks will start to make themselves present, revealing an unshakeable rift that wasn’t there before.

As a girl, it was always difficult to be one or the other. Being shy or girlish would brand you as “maarte,” but on the other hand, being loud and aggressive would cause the adults to admonish you for “not being enough of a girl.” Through a more mature lens, these may seem more like the lighthearted jests they were intended to be—but for that little girl only on the precipice of learning who she was, it was hard to not feel humiliated. It was hard to be the butt of the joke, the odd one out, and the subject of oddly-strung remarks, that it just became easier to fall in line.

- I’m sorry that you had to grow up too soon.

“You’re so bright for your age!” exclaims a nosy tita during a family gathering. It’s a well-meaning compliment, but these days, most people seem to measure skill by how much farther you can outgrow and outdo your peers. Covertly, it fostered a norm that favored being “mature for your years,” —scorning what was childish and carefree, and replacing it with a need to grow up.

Toy kitchens and baby dolls will soon be replaced by elaborate makeup kits and expensive bags. Looking back, you were too young to be scrutinizing your flaws and having to ask yourself: “What was wrong with me?” Gleaming models in TV commercials and videos online will point out the things you lack: perfect long hair, clear skin, a pretty face—all the features that society holds to be attractive. To that young Filipino girl, it didn’t really matter if that Western model was ten years older or several brand endorsements richer. It was easier to thrust yourself into a consumerist fever of having the newest and most expensive trends—of having to want more.

- I’m sorry that until now, the world still asks too much of you.

“You must be charming (conventionally pretty), well-composed (not boisterous and overly-emotional), and dignified (always perfect)” is a statement that might not come in glaring obviousness as it had in ancient times, but it is still subtly implied in every unwarranted comment, unnecessary rule, and archaic tradition that has limited women since girlhood.

Being a woman, it seems, is living a lifetime of contradicting expectations of what you should and shouldn’t be. Perhaps, some things aren’t too different. You still have to be caring and docile—but not too much to be considered weak; you still have to speak your mind, but you can’t be too assertive. On the other hand, for how much the concept of maturity is venerated for little girls, women must be obsessed with maintaining their youthfulness and treating all signs of aging with disdain.

One is soft, while one is tough. One is old, while one is young. But it’s hard to be one or the other in a world that relentlessly scorns its women all the same; thus, just like any other evolutionary adaptation, another generation of young girls will inherit this obligation for ambivalence from the women that came before them—forced to overcome a covert battle orchestrated against their favor.

Mothers will continue to be strict and uptight for the sake of their daughters—scrutinize their every move, and reprimand even the slightest of mistakes—when in truth, it is the world that requires changing. We will not need to fail another generation of little girls if we begin to acknowledge the flaws in our society now, and work together to overhaul the conventions that continue to box women into an idea that they don’t need to become.