by Aliya Janeo

There is a difference between sympathy and empathy.

We can only uphold the memory of Martial Law with all the sympathy we have in our bodies, because even after a week-long commemoration of this period in Philippine history, we students will never understand this era with as much depth as those who have seen the country’s dark days themselves. No matter the age, Martial Law took the lives and mindsets of the Filipino people by storm— the People’s Power Revolution that followed all the more so.

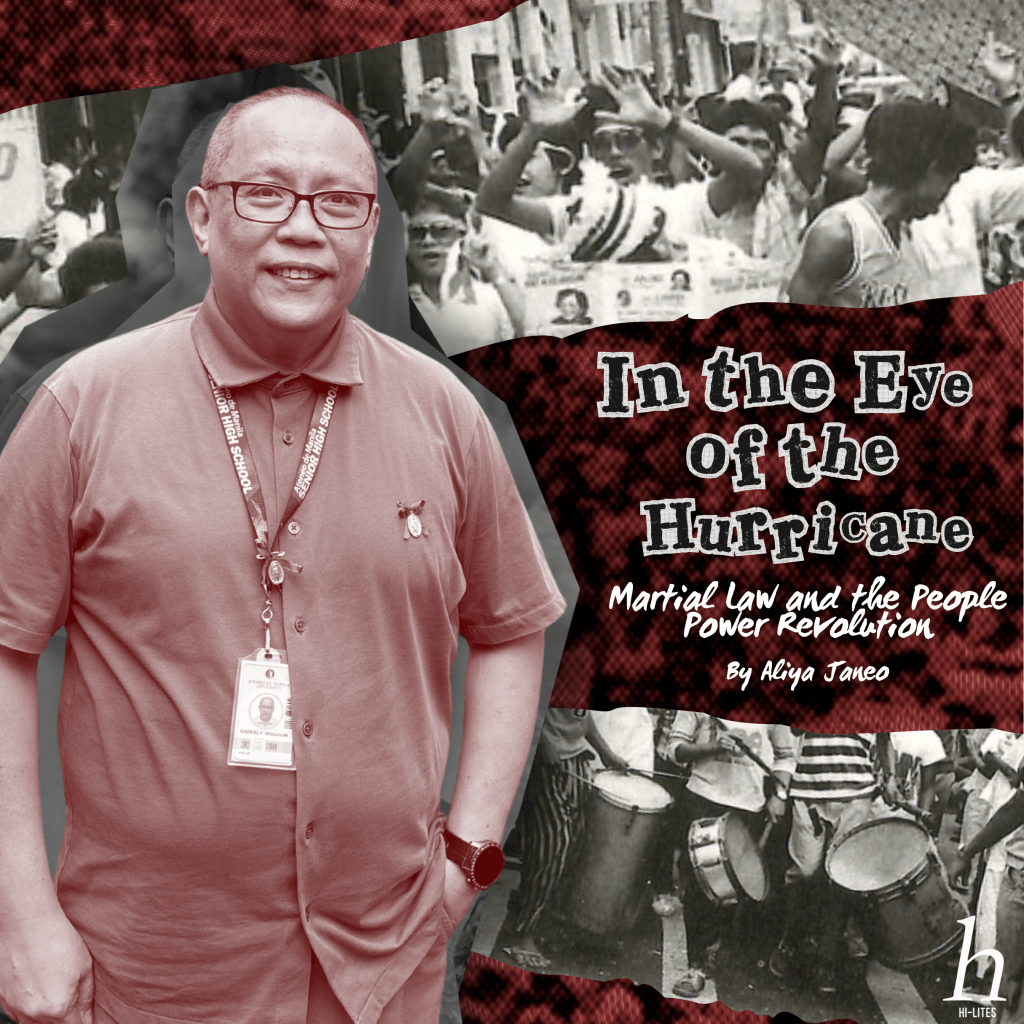

Mr. Gabriel Mallillin, Computer Subject Area Coordinator in the Ateneo Senior High School, is someone who has lived when Martial Law came to be, and has joined his fellow countrymen in activism as the Marcos dynasty was trampled.

Compared to his participation in marches and protests in college, he admits the childhood he lived under Martial Law wasn’t one that contributed much to the person he is today. Still, these anecdotes from Mallillin’s life are nonetheless an eye-opener and an inside look into a life under the rise and fall of a dictatorship.

A Quiet Drizzle

“I was deprived of my rights as a 7-year old child because I wasn’t able to watch my favorite cartoons on TV.”

This is something Mallillin has shared to his moderating class, 11-Borja, as he discussed his childhood during the Martial Law period. Admittedly, to him this was a more quiet time that did not contribute much to the person he is today, however, there are still memories of this era that stick to him.

He recalls his father having coupons, to purchase gas, due to the fact that the prices of such necessity skyrocketed during Marcos Sr.’s reign amidst the country he left bankrupt and impoverished. Besides this, he detailed the need to sing songs of propaganda in school such as the loyalist theme, “Bagong Silang,” an additional attempt to instill certain values in the Filipino people.

The 11-Borja moderator also details that as the media blackout ended, memories of how well-known comedian and actor, Ariel Ureta, was sent to Camp Crame after making fun of a Martial Law slogan. Instead of the government-established “Sa ikauunlad ng Bayan, disiplina ang kailangan,” Ureta mocked this in a parody by stating, “Sa ikauunlad ng Bayan, bisikleta ang kailangan!” In response to this comment, he was made to bike in Camp Crame for a whole day as a jesting punishment.

Mallillin may have lived his childhood during a time where violence was silent, but a growing storm brewed inside his heart and that of many Filipinos once these injustices came to light and the voices of the quiet were amplified. Though his rights as a child to entertain himself and watch cartoons was restored after the blackout, this could not stop the brewing storm that would form as he grew older.

The Winds of Activism

“Because of all the violations of human rights, of how people were poorer during Martial Law—there was actually no freedom to speak of.”

On January 17, 1981, via Proclamation No. 2045, Martial Law in the Philippines was officially terminated. Along with the end of Martial Law came the end of silence. According to Mallillin, although the lifting of Martial Law was a quiet process, what followed was far from it. He states that people were now vocal of Marcos’ rule and defined it as what it was: a dictatorship.

The Computer SAC states how he was involved in several anti-Marcos rallies in his college days, especially after Ninoy Aquino’s assassination and the poverty Marcos Sr. left in his wake. Martial Law had been lifted, but there was no freedom to be found when the country was shackled by the aftershocks of his reign. Although he mentions how he was unable to attend the funeral march of the late senator, he says how he marched in the many protests that followed; something Ateneo was at the forefront of.

He describes the more peaceful protests that Ateneo was attuned to, stating how it was more so a representation of the middle class than that of UP— who were spokespersons for the lower class who were rebellious in amplifying the voices of marginalized members of society who became poorer than they actually were.

After his college days, he depicts memories of attending the 20-kilometer march for the late Evelio Javier, bringing his coffin from Baclaren church to the Ateneo de Manila campus. Javier, one of the ASHS’ most distinguished alumnus and namesake of the ASHS’ most prestigious award, was an advocate for human rights who campaigned for Corazon Aquino and Salvador Laurel in the snap elections. Due to his vocal criticisms of Marcos Sr. ‘s presidency, he was assassinated just days after the elections.

At the time of the march, the EDSA People Power veteran as a Legal Management major, was amongst those who carried the responsibility of marshalling the ranks should there be any instances of violence. With this responsibility, he had with him a compilation of contact details of human right’s lawyers in the event of an untoward incident.

“Ibon mang may layang lumipad / Kulungin mo at umiiyak,”

This is a lyric from “Bayan Ko,” by Freddie Aguilar, a song that played on the PA system during the ASHS Sanggunian’s commemoration of Martial Law. This song made him reminisce about his college days prior to the EDSA Revolution, when he and his progressive classmates organized a class walk to gather small groups of people to discuss relevant and pressing issues. He details how they would start the day with a flag ceremony, and sing “Bayan Ko,” instead of our national anthem, “Lupang Hinirang,” due to the fact that “Lupang Hinirang,” was a song for freedom and they were not free.

Though he didn’t understand the time of Martial Law when he lived in it, Mallillin describes his childhood as somewhat of a ‘foreshadowing,’ for what he was going to comprehend later on. His college days gave him the opportunity to further educate himself and shed light on the kind of era that he himself had lived in— a note we should take for ourselves to keep the memory of our history alive within and outside the walls of the ASHS.

A Sunrise in Blue and White

“It is one thing to be able to actually protest and show signs of indignation. I’m not sure the understanding is there, but at least meron.”

Before becoming a Computer teacher, Mallillin was once a Filipino teacher. He recalls teaching Lualhati Bautista’s book, “Dekada 70,” a more graphic fiction piece based on real life events. Teaching pieces such as this gives students now insight into an era they themselves never lived in.

Yet, the MIL teacher believes that the ASHS is unable to fully understand Martial Law as it was, as we students were born in times far more fortunate than this point in history. Still, he appreciates the yearly commemorations of Martial Law, and praises our grasp on history; which he claims rivals that of other people in our generation who may not be as aware.

He believes that there should be more mediums to learn about Martial Law, especially since we as a country face multiple cases of false information and historical distortion. He separates distortion from revisionism, stating that it is alright to revise facts to correct misconceptions or inconsistencies; completely different from distortion which is constructing information out of thin air to manipulate perception.

Despite us students not being able to fully understand Martial Law and the complete situation its victims lived in, we can all live with a sense of sympathy and fulfill our responsibility to keep ourselves educated. Mallillin himself was fortunate enough to not live through the hardships of this dark time, but acknowledges the importance of being aware and looking at the perspective of others going through more tumultuous times.

The ‘Never again, Never forget,’ slogan is one Mallillin states rivals the claims of praise that try to overshadow that of the Marcoses’ conjugal dictatorship. We should open our eyes to the history that was once concealed from us and learn from the past. This slogan was made for a reason, and there are still people alive to tell the story. No clouds will obscure the light this time around, and as Mallillin states:

“If we forget, we might put on a pedestal, someone who is not deserving.”