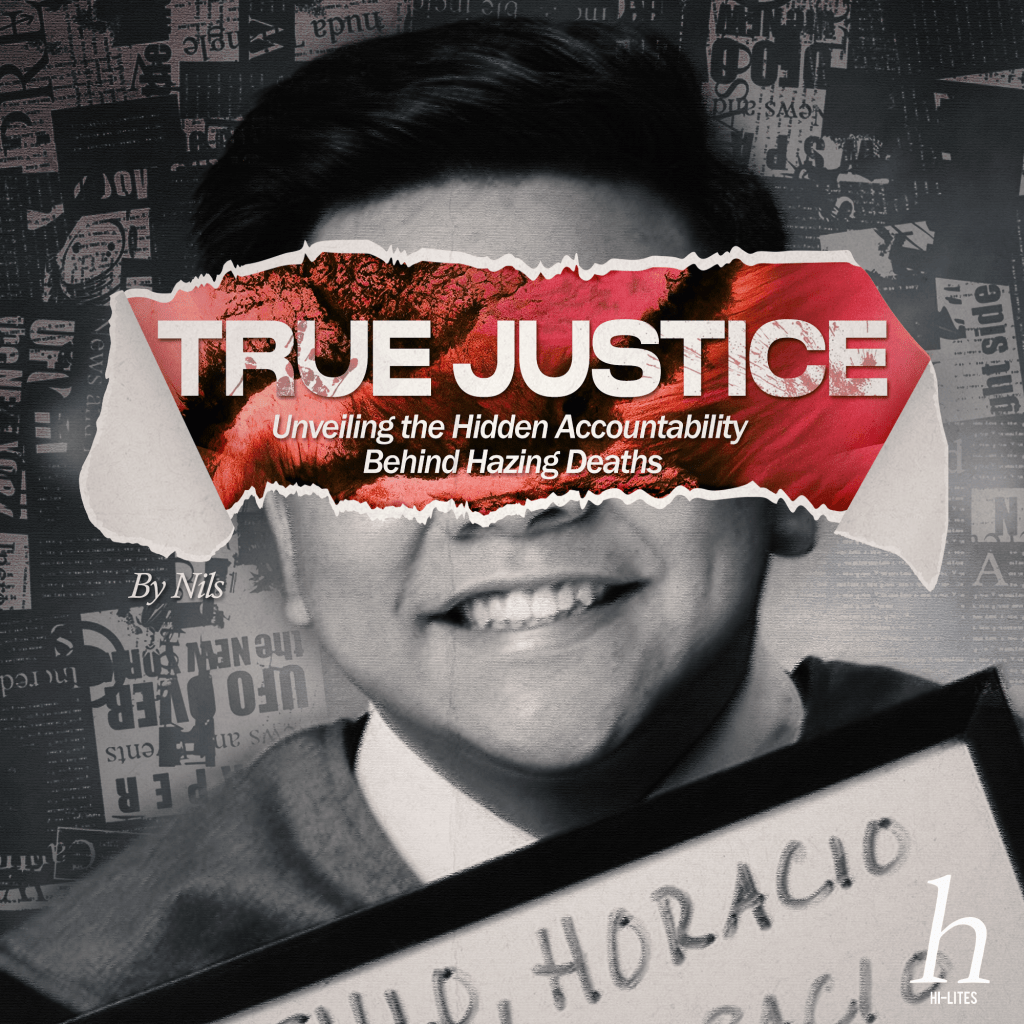

by Nils

#JusticeForHoracio

After more than seven years, justice has finally been served. The Manila Regional Trial Court convicted ten members of the Aegis Juris fraternity on October 1, 2024, for their involvement in the 2017 hazing death of University of Santo Tomas (UST) law freshman Horacio “Atio” Castillo III.

However, this verdict alone is not enough for Atio’s mother, Carmina Castillo. She calls for accountability that extends beyond the convicted fraternity members; she is holding UST and its administration responsible as well. “The school failed to protect our son…,” she declared, pointing out that it is not merely the individuals who committed the violence that should be held accountable but also educational institutions that fail to ensure the safety of their own students.

Yet, this issue is not just about UST; it concerns all educational institutions, often regarded as a ‘second home,’ for students, that fail to protect them from the culture of violence that exists within their own walls.

Brutality in Disguise

Hazing, in the context of the Philippines, is defined as any act that inflicts physical or psychological harm on an individual as part of an initiation process into an organization, fraternity, sorority, or any similar group. According to a study in 2017, many scholars asserted that this act is now part of the culture of higher education and has become a serious concern for administrators and authorities. Hazing has led to neophyte injuries and deaths in the country’s schools from 1954 to the present. More specifically, there have been at least 17 deaths due to hazing in the past decade. But despite all the reports of injuries and deaths, fraternities continue to thrive, and why is that? These fraternities offer students the advantage of being open only to a selected few—the advantage of having exclusive access to networks that can open doors not only to better jobs but also to greater opportunities for advancement. In the feudal society of the Philippines, connections often outweigh qualifications. Because of fraternity ties, many believe that this shortcut to success could justify the risks associated with hazing and violence.

Atio’s death in 2017 prompted the passage of the New Anti-Hazing Law on June 29, 2018, or the Republic Act 11053. It amended Republic Act 8049—the old Anti-Hazing Law—which already provided for a prison term of reclusion perpetua (20 to 40 years in prison) for hazing rites that would result in death, which was received by Atio’s murderers. The new law introduces new guidelines on initiation rites and harsher penalties for those who will not abide by it. However, it has not stopped hazing deaths, as other young men died due to hazing after Atio.

The law meant to prevent fraternity violence has failed to stop underground initiation rites that inflict severe harm to neophytes, some even leading to deaths. Why do these fraternities feel the need to inflict unnecessary pain and suffering on individuals before they can be considered “brothers?” Such mentality only perpetuates a cycle of brutality masked as brotherhood. And it demands serious actions before more students become a part, not of a fraternity, but of a group of people who have lost their lives as a result of physical punishment and torture brought upon them by those they trusted to be their brothers.

The Culture of Violence

RA 11053 increases the accountability of school administrators by requiring them to establish guidelines for approving or denying the conduct initiation rites. Organizations that wish to hold initiation rites, even if they don’t involve hazing, must submit a written application to the school authorities in order to conduct them. The law also introduces harsher penalties such as reclusion perpetua and a PHP 3 million fine for hazing that results in death, rape, sodomy, or mutilation. While hazing that does not result in these harms would still mean the penalty of reclusion perpetua and a PHP 2 million fine for those who are involved, including the officers of the organization and its adviser. Moreover, any form of approval, consent, or agreement signed by the neophyte will be voided.

Despite the ban on hazing, fraternities continue to exist because the 1987 Constitution grants them the right to form organizations for lawful purposes. Authorities cannot completely outlaw fraternities, as this would violate the constitutionally protected freedom of association. Even though hazing is prohibited, fraternities still thrive and operate, with some members engaging in underground initiation practices—often involving violence.

The reality is that hazing has now become a tradition in most fraternities; it is also a cultural problem, not just a legal one. “What needs more attention is the ‘pervasive belief in the culture of hazing,’ that leads students to think that ‘harsh physical testing is a requisite to become a deserving member because previous generations of members went through the same,’” Filomin Gutierrez, a sociology professor at the University of the Philippines Diliman who has extensively studied fraternity culture, pointed out. These toxic beliefs are now passed on from one generation to another. For as long as it exists in the minds of fraternity leaders, the cycle will continue. Implementing harsher penalties alone cannot address this. It requires cultural and educational reforms beyond just legal measures.

The Students’ Second Home

Last year, on February 28, John Matthew Salilig, a 24-year-old chemical engineering student at Adamson University, died as a result of harsh initiation rites by the Tau Gamma Phi fraternity. Fraternities have been banned in the university “for many, many years,” according to university president Fr. Marcelo Manimtim. However, the university admitted that they were aware of the fraternity’s ‘alleged presence,’ on campus, which raises the question: Why were these activities not stopped despite the university’s long-standing prohibition? Although fraternities are technically prohibited based on policies, it is the school’s responsibility to continue monitoring suspicious activities done by students, whether or not it is confirmed.

Similarly, the UST law dean, Nilo Divina, is an ‘inactive’ member of the Aegis Juris fraternity, whom Atio’s parents filed a complaint against. However, it was dismissed by the Department of Justice (DOJ) due to lack of evidence. “The university and the faculty have always implemented and upheld policies that promote the safety and welfare of all students. Unfortunately, no institution is spared from the actions of individuals who choose to disregard these measures,” Divina disagreed with Carmina after she stated that the institution failed to protect Atio. If policies were in place, why did the Aegis Juris fraternity operate under UST’s radar for years? The fraternity’s co-founder even bravely expressed that Atio’s case is a “test of how strong their bond as fraternity members of the Aegis Juris is.” Well, fortunately for them, they can continue this bond for another 40 years behind bars.

These institutions simply enforcing policies is not enough to ensure the safety of the students—or, more specifically, to eliminate hazing; it requires active monitoring, especially when university officials themselves are aware of the fraternity’s presence in their campus. Educational institutions are called the ‘second home’ of students for a reason—they should foster environments that promote learning and personal growth. Their responsibility goes beyond merely the implementation of rules; they must commit to creating a culture that prioritizes student well-being rather than assuming students will adhere to a set of rules without further support. More importantly, they should not be turning a blind eye to what is already obvious. They could have prevented these deaths if they had done something beforehand.

Justice requires change.

Every school year brings new reports of hazing victims in the Philippines, and hazing remains the number one agent of violence in higher education campuses. It is not because it is tolerated. Fraternities are, in fact, banned in most universities. Yet, this only forces them to operate underground. Thus, prohibiting such groups from openly operating only pushes them to perform these initiation rites unchecked and hidden from authorities. The New Anti-Hazing Law was enacted in response to the tragic death of Atio in 2017, but hazing has not ceased. This law mandates reclusion perpetua for acts of hazing that result in death, as in Atio’s case, but the violence continues underground.

The laws exist to protect students, but educational institutions must go beyond merely enforcing them. The deaths resulting from hazing reflect a deep-rooted culture of fraternity violence fueled by powerful networks and societal advantages. Institutions need to actively monitor fraternities, especially when aware of their presence, like in the case of Salilig, who died in 2023 despite a ban. It is crucial for universities to implement policies while fostering a culture of non-violence and inclusivity to deter students from dangerous initiation rites. On the other hand, students also should not believe that violence is the answer to their success or that they need to endure punishment to belong. Such beliefs only contribute to a culture that devalues their worth and undermines their safety, ultimately leading to tragic outcomes such as deaths that could have been prevented.

Justice for these young men cannot merely be about punishing the perpetrators; it requires a fundamental shift in how fraternities operate and are perceived. Educational institutions, as students’ “second homes,” must create environments that prioritize learning, safety, and personal growth. Their responsibility is to protect students by fostering well-being over traditional ties or fraternity connections. Failing to do so makes them complicit in the violence they claim to oppose. Justice requires more than punishment—it demands systemic change.