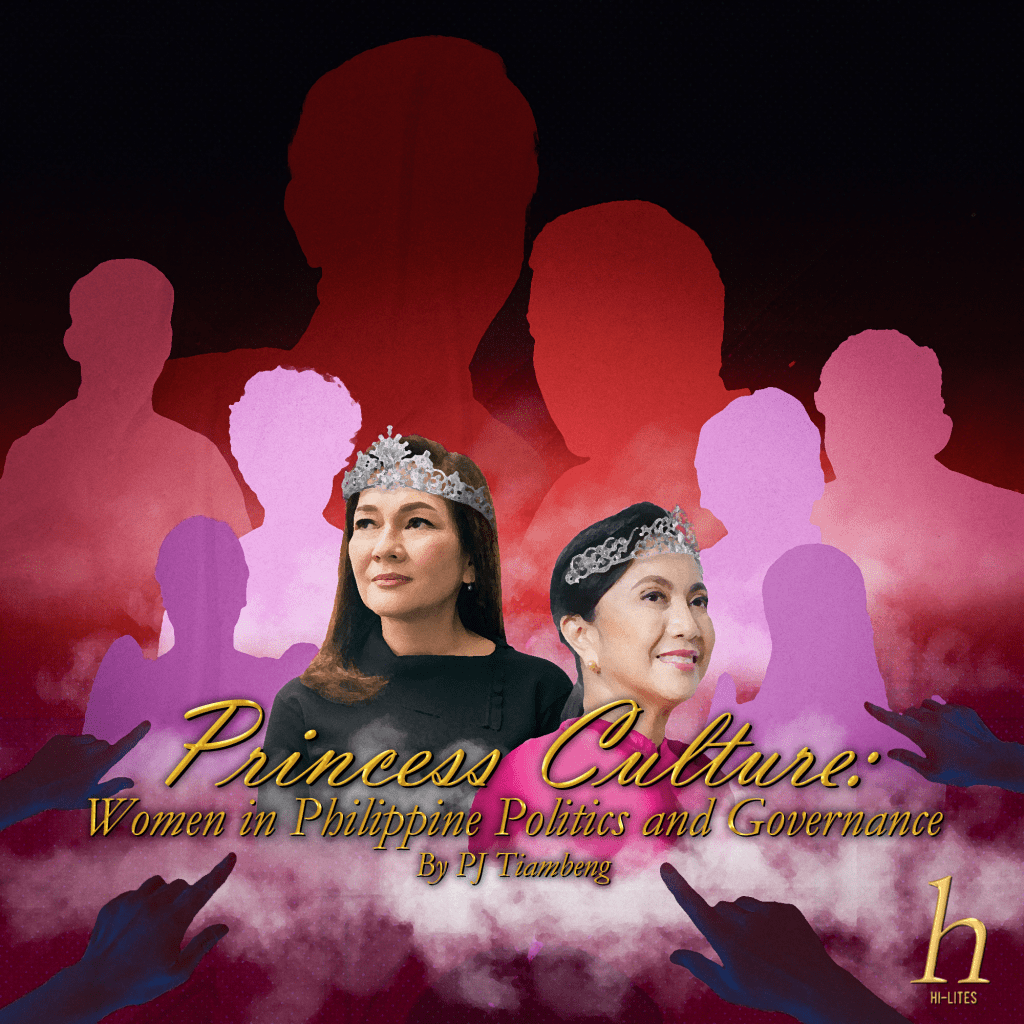

By PJ Tiambeng

In the pre-colonial Philippines, women and men were respected equally in terms of their own roles and statuses in society. Then, entering into the 1500s, as colonization and colonialism came about in waves, western influence brought about patriarchy, teaching our ancestors that women were “inferior” to men and changing their position in society to one that we have yet to fully recover from. Yet, that does not mean that in all this time, Philippine women have suffered in silence — from the labor organizing of the working women under foreign rule to the women-leaders that we have now — generations of Filipina feminists have fought for their rights and their voices to be heard.

We have indeed come a long way from the 1500s. In the 1930s, after much struggle, women were finally allowed suffrage, with more women being elected into office in the years after, including our two female presidents.

“[Former Vice President] Leni Robredo built her campaign on elements that are traditionally associated with feminine gender roles…the colour pink… the idea of ‘radical love.’ While her rivals projected machismo and strongman imagery, she took the opposite approach… the fact that she was able to garner about 14.8M votes speaks to the fact that while we are far from rejecting machismo populist rhetoric, the Philippines has progressed enough to recognize that there are other factors that make a good leader,” Ma’am Mika De Guzman, a teacher in the Social Sciences Department of the Ateneo Senior High School, pointed out.

Nevertheless, this freedom still comes with socially and culturally ingrained misogyny. In 2022, a study found that most Filipinos still prefer men over women as politicians.

A True Democracy

“Women, of course, are crucial to politics because their experiences and unique insights lend further depth of understanding when it comes to creating good public policy. It’s pretty simple: if we are as committed to upholding democracy and good governance in our country, then women must always have a seat at the table. The latest PSA numbers place the population of women in the Philippines at about 6.7M. That’s a good-sized portion of the population, no? Tunay ba ang demokrasiya natin kung wala silang boses? (Is it true democracy if they have no voice?),” De Guzman said.

Having women in these leadership positions upholds democracy as they are already half of the country’s population, further emphasizing that their representation and participation are needed for sustainable progress for all in the different political processes and decisions. They also aid in the development of social welfare. Women’s visibility is symbolically valuable as they serve as role models for future generations of girls and young ladies who wish to serve the country as well.

De Guzman pointed out that “The Senate President, Pro Tempore, as well as both Majority and Minority speakers are all men.”

Since 2019, 28% of the House of Representatives and 29% of the Senate have been women. When including local government leaders, 23% of elective positions in the country are women. Still, De Guzman pointed out “The Critical Mass Theory states that a minimum of 30% female representation in decision-making bodies is often required to create meaningful change in governance and culture…” The proportions of women to men in the government bodies still fall short of this quota. This lack of representation also discourages women from participating in politics.

Masked Progress

In the Philippines, The United Nations Development Programme found that “99.5% of the population, including 99.33% of men and 99.67% of women, hold biases against women.”

Even when it came to Robredo’s 2022 run to be President, some said that they would not vote for the former Vice President because she was a woman, as though this meant weakness.

Unfortunately, women in politics are often recognized in relation to their politically involved husbands or male family members. And female politicians who come from political families tend to lean more towards the benefit of their family than addressing women’s issues — highlighting the need for truly meaningful participation.

To make matters worse, social media has reinforced misogyny through anonymized threats, gendered disinformation (false or misleading information attacking women based on their identity as female), and gender stereotypes. The sad truth is that, instead of calling out men’s role in their own families, women often even have to play into these stereotypes to be more appealing to voters.

Additionally, misleading information portrays women as unfit for leadership roles and a threat to democracy, limiting much of the population from participating in politics. Women are further discouraged by the persistent “Violence against Women in Politics (VAWP),” as coined by Mona Lena Krook in 2020. A big part of VAWP in Philippine politics is semiotic violence, such as ridicule or slut-shaming during Rodrigo Roa Duterte’s presidency and the 2022 elections with the dissemination of fake sex videos of former Senator Leila de Lima and former Vice President Leni Robredo’s daughter.

In the political institutions themselves, systems create an environment holding back female politicians and benefiting their male counterparts more. This can be seen through the emphasis on seniority for committee chairpersonships, gender stereotypes, a lack of gender-sensitive parliamentary rules, and incidents of sexism, misogyny, and micro-aggression, especially in the House of Representatives or the Senate, despite the vocal “support” that their male colleagues may have for women empowerment.

“The Philippines’ social structures tend to be hetero-patriarchal (where political practices are viewed in dichotomies between the sexes)… traditional male and female gender roles are reinforced… political leadership is often viewed as a man’s job (strength, machismo and authoritarian tendencies as attributes of a good leader)… perhaps the Filipino people also tend to view the nation in terms of it being a family. If the nation is a family, then who better to lead it than a father? A good father rules with tough love,” De Guzman emphasized, referencing research by Evangelista (2017).

Abante, Babae!

“Actually! What’s really cool is that many women are already very involved in dialogue and decision-making sa local level. Women tend to be key figures in their communities, even if they do not hold formal leadership positions. Ang daming mga barangay na very powerful ang mga samahan ng mga kababaihan, kasi they have their fingers on the pulse of their community. Sila kasi ‘yung mga laging naka-stay sa bahay, laging nakiki-salamuha at nakikibahagi sa iba pang mga miyembro ng komunidad nila, kaya alam na alam nila ang kaganapan sa barangay,” De Guzman added. (“There are many barangays wherein women’s organizations are very powerful, because they have their fingers on the pulse of their community. Because they are always the ones staying in the house, socializing and engaging with other members of the community, so they really know what is happening in the barangay.”)

In the end, our celebration of Women’s Month last March should go beyond the time itself. We must call on our leaders to develop legislation defining and fighting against VAWP. It is the women’s right for their voices to be heard — to have a seat in governing bodies.

We must continue fighting for our women to be represented and our female leaders to be celebrated. And not only for the fact that they are women and leaders, but also the fact that they will fight as well for the rights, agendas, and values that uphold women’s integrity in our Philippine society.

“I think this goes back to creating a culture where women are encouraged and empowered, instead of belittled and brushed aside. Creating or changing culture means changing people’s mindsets and behaviors. We can start with the way we view positions of leadership. We could change the way we raise our little girls. When a child says she wants to become a princess, we can encourage the idea that princesses are also rulers of kingdoms. Princesses are pretty and soft, yes! But they are also smart, capable, and compassionate leaders. Girls don’t just have to be one or the other! They can be both! And good rulers don’t have to be strong and tough and disciplinarian warlords! Good rulers are actually supposed to be kind, fair, and committed to restorative justice,” De Guzman concluded.