By Feebee Mariposa

By Ellianna Custodio

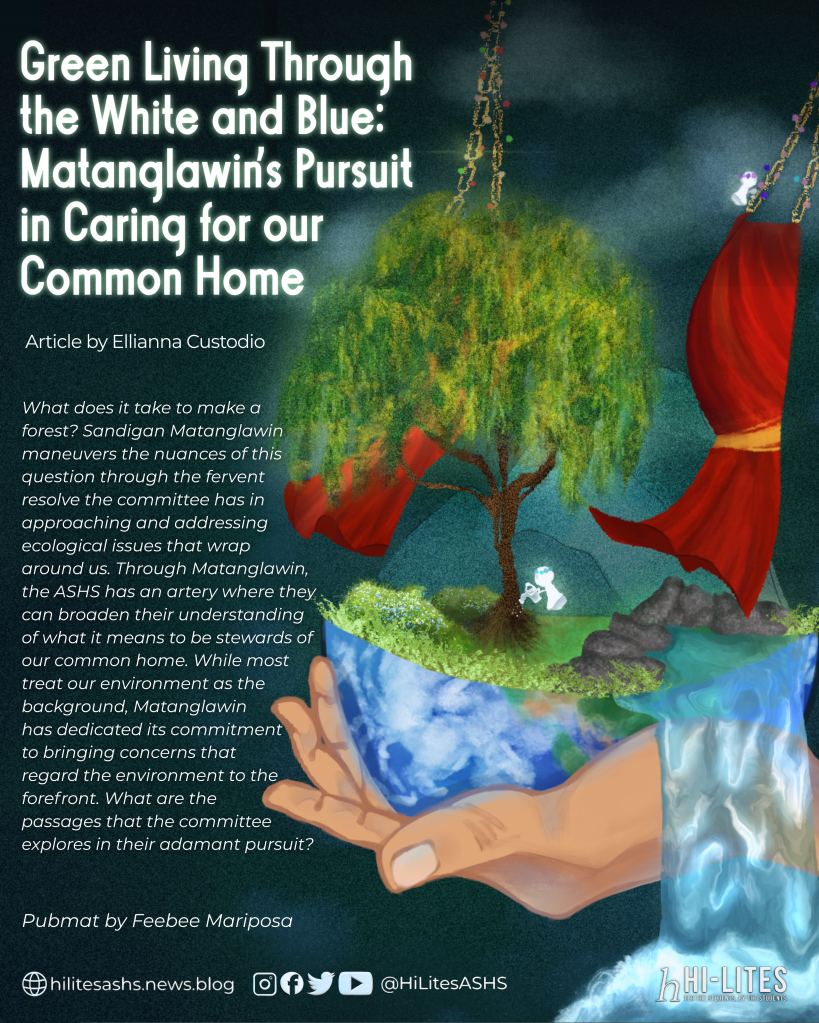

More often than not, we treat our world as a backdrop, passively acknowledging its existence while it incessantly provides us our resources and needs as we go about our lives, answering to other requisites. In such a fast-paced world, it is easy to get swept away by demands and sweep everything ‘less important’ beneath the rug — our environment is no stranger to the actions of the latter. But while most continue treating our surroundings as a mere setting, Matanglawin has set their hearts to steering this perception to underscore the importance of seeing it instead as a living character.

Being one of the six Sandigans, Sandigan Matanglawin is a committee that does more than just campaigns for sustainable practices; it has also been complicit in helping the ASHS student population develop a profound conscientiousness for how they approach our environment. They’ve remained steadfast in their espousal, recognizing the relevance of what they are championing, now more than ever.

As Laudato si’, the encyclical written by Pope Francis to address ecological concerns, became a decade old this year, Matanglawin has since maintained its proactiveness in taking our environment from the backdrop and bringing it to the forefront of our minds, just as how it has always been within our lives, unbeknownst to us.

The Wellsprings of Advocacy

Looking inwards, Matanglawin brings environmental issues to the foreground by highlighting the small, seemingly unnoticeable actions we do that can have dire effects in the long run. Despite being all around us as the very realm we move within, the cries of our environment have faded behind personal priorities and undertakings we deemed to be weighty, but Matanglawin has been steadfast in bringing sustainability advocacies and practices closer to the Atenean context.

“The advocacy aims to serve as a platform to address pressing environmental issues to take action and form movements so that the community can contribute to a positive and sustainable change,” Lorenzo Liwanag, the Overall Head of Matanglawin, explicates the goals the committee aims to achieve. Liwanag from 12-Pantalia expresses how the committee has served as his home, reminiscent of his life before. Having moved from a quaint province centered on agriculture to the bustling roads of the city, Liwanag took up his position to help form that same comforting environment from his province for others, and Matanglawin became his primary avenue in bolstering sustainable practices.

The committee’s mission is scaffolded by the inseparability of human and nature, as elucidated in Laudato si’ through the concept of integral ecology. During these times where such issues that concern our common home are treated as detached from our functionality as humans, Matanglawin has been a constant amplifier of the intertwinement between us and the environment, magnifying the ripples caused by seemingly small, insignificant actions. Rafaella Suplico of 12-Sullivan, the Communications and Research Head of Matanglawin, describes the organization as a place in the ASHS where care is translated into concrete action.

“Matanglawin’s mission of fostering awareness about the current situation of the environment and providing platforms to ease this is what drew me into the organization–to remind people that even small actions, like properly segregating trash, create ripples of impact.” Suplico states when asked why she felt drawn to the committee.

Undergirded by the interwoven subjectivities that waver between our environment and the systems that make up our operations as humans, Matanglawin lays its foundation in their mission to cultivate a community that takes our environment out from the peripheral perspective and integrates it into the vital aspects of our lives. How then do the wellsprings of these sentiments materialize and stream down into tangible initiatives?

The Streams of Action

“This committee serves as a reminder and encouragement that we Ateneans do care, and that there are ways to help!” MJ Montoya, the Branding Head, from 12-Walpole bridges the committee’s presence with the student body, “Just contact us, participate in tree planting or anywhere, or donate old papers to our paper drive! It’s proof that we are concerned and we are doing something about taking care of our planet.”

Matanglawin champions this ecological conversion through discussions and initiatives that call people to pay heed to the ways we unconsciously harm our common home. Through such projects, the committee fosters more and more minds to think sustainably — catalyzing actions that reflect the beliefs ingrained in Laudato si’, actions that endow the greater good.

The Habitat is an example of these initiatives, being Matanglawin’s online newsletter, The Habitat is the committee’s avenue in disseminating pertinent information that promote and propose sustainable solutions while also addressing ecological issues. Through The Habitat, Matanglawin has been able to combat concerted unfamiliarity about contemporary topics that range from the global level trickling all the way down to localized contexts, more particularly, the approaches taken by the university towards its objective of being a sustainable institution.

Another notable initiative of the committee is the Linis-Sea Beach Cleanup, an annual project where members of Matanglawin would travel to beaches to collect and pick up trash along the coastal lines. Suplico expresses the rationale behind this project, “Marine pollution has to be one of the biggest issues our Mother Earth faces with the damage of ecosystems and wildlife that all live in the sea. Sandigan Matanglawin aims to foster environmental awareness and community action by the beach clean up beyond the campus through community involvement and collaboration.”

Such student-led actions are aligned with the fifth chapter of Laudato si’, wherein imperatives are given for collective actions that don’t impede progress, but rather work concurrently with advancements to achieve both development and sustainability. Matanglawin roots their initiatives in these sentiments, to which Liwanag contends that the pursuit for environmentally conscious technology and innovations are as crucial as the development of such technologies taking sustainability into account.

Liwanag states, “I firmly believe that technological advancement and ecological mindfulness are not mutually exclusive, but instead go hand in hand in building a better future.”

“Technology is a big part of how Sandigan Matanglawin communicates their advocacy to the student body.” Suplico states, to which she expounds how digitized vessels have been the committee’s primary avenue to relay information to the ASHS student populace regarding events where they can participate in their path towards communal care for the common home and publishing issues of The Habitat.

But predicaments persist, even with efforts, Matanglawin’s scope has met its limitations — not as a result of the committee’s shortcomings, but rather because of external impassivity in rewiring their ways for more eco-wise habits. Participation from students beyond the organization has been limited and garnering genuine interest has been posed as a challenge for the committee. However, Suplico contradicts this by responding divergently, “This only motivates us to create more engaging and relevant projects that connect sustainability with students’ daily lives.”

Each exerted effort has shaped the committee’s progressing pursuit, whether that may be through digital publications or hands-on work. Sandigan Matanglawin has planted their advocacy into fertile ground, one that is nurtured by their perseverance amid complacence towards ecological concerns. Such constraints have sharpened Matanglawin’s mission towards an ecologically concerned community, clearing the skies ahead for the committee’s developing story. What are the branches that have splintered from this and the fruits that Matanglawin aims to bear?

The Estuary Ahead

“As Pope Francis reminds us in Laudato Si’, we are called to care for our common home because it is the only one we have.” Suplico recalls what is enshrined within the aforementioned encyclical.

To Sandigan Matanglawin, our common home will always be more than just the backdrop; It will always be a living character, with attributes, woven into our narratives just as we are woven into the fabric of its narrative. Our common home is a recurring motif in each of our stories, deserving of heed that does not just end in reposted social media posts or hollow proclamations for sustainability — neither of which is reflective in the work that Matanglawin has done during its existence thus far in the ASHS.

Commitments that champion ecological advocacies like Matanglawin are now more relevant than any other era during contemporary times. It is especially more significant that such organizations are spearheaded by the youth, as it couples conceivable external issues with the context of our generation. Matanglawin is a concrete emblem of our capabilities as the youth to reenvision apt solutions amidst the continuous increase of environmental degradation.

“I envision the committee to further continue and grow with genuine love and care for the environment. Prioritizing plans or thinking of ways to help the environment whether it be big or small, continuing to protect and preserve God’s creation,” Montoya illustrates the objectives that lie ahead of Matanglawin.

The stewardship that our common home calls for is one that encompasses our time, energy, and careful consideration. Sandigan Matanglawin has shown through its initiatives the waves that can be caused from a small drop of water, the fortified trees that can sprout from the smallest of seeds, the change that can be borne out of one small alteration in the lifestyle we lead. Our narrative as presiders of this world isn’t independent from the implications that concern it; to care and love for our environment directly translates to caring and loving for one another, and vice versa.

“My work in Matanglawin helped me recognize that achieving these goals isn’t possible without combined effort,” Liwanag reflects on the inferences he has discerned during his time in the committee. He emphasizes the significance of collectivity, intertwining ideas with like-minded people who share the same advocacies to better inform those who do not have a comprehensive grasp of the dire state our common home is. “To make a forest, it takes many trees.”

As what has always been gently taught to us, Laudato Si’ quotes in Chapter 6 on Ecological Education and Spirituality, “Living our vocation to be protectors of God’s handiwork is essential to a life of virtue.”